Wells Cathedral

| Wells Cathedral | |

The west front, completed c. 1250, has about 300 medieval statues; many of the figures, and their niches, were originally painted and gilded |

|

| Basic information | |

|---|---|

| Location | Wells |

| Full name | Cathedral Church of St. Andrew |

| County | Somerset |

| Country | England |

| Ecclesiastical information | |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Province | Canterbury |

| Diocese | Bath and Wells |

| Diocese created | c.909 |

| Bishop | Peter Price |

| Dean | John Clarke |

| Organist | Matthew Owens |

| Website | www.wellscathedral.org.uk |

| Building information | |

| Dates built | 1176–1490 |

| Architectural style | Gothic (Early English) |

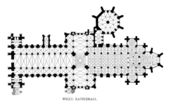

| Length | 116.7 m (383 ft) |

| Length (nave) | 49.1 m (161 ft) |

| Length (choir) | 31.4 m (103 ft) |

| Width across transepts | 41.1 m (135 ft) |

| Width (nave) | 11.5 m (38 ft) 24.9 m (82 ft) including aisles |

| Height (nave) | 20.4 m (67 ft) |

| Height (choir) | 20.4 m (67 ft) |

| Towers | 3 |

| Tower height(s) | 48.7 m (160 ft) (crossing) |

Wells Cathedral is a Church of England cathedral in Wells, Somerset, England. It is the seat of the Bishop of Bath and Wells, who lives at the adjacent Bishop's Palace.

Built between 1175 and 1490, Wells Cathedral has been described as “the most poetic of the English Cathedrals”.[1] Much of the structure is in the Early English style and is greatly enriched by the deeply sculptural nature of the mouldings and the vitality of the carved capitals in a foliate style known as “stiff leaf”. The eastern end has retained much original glass, which is rare in England. The exterior has a splendid Early English façade and a large central tower.[1][2][3]

The first church was established on the site in 705. Construction of the present building began in the 10th century and was largely complete at the time of its dedication in 1239. It has undergone several expansions and renovations since then and has been designated by English Heritage as a grade I listed building.[4]

Peter Price is the current Bishop of Bath and Wells having been appointed in 2001; and John Clarke took over as Dean in September 2004 after previously being principal of Ripon College, Cuddesdon, Oxford.

Contents |

History

Early years

There is archaeological evidence of a late Roman mausoleum on the site.[5]

The first church was established here in 705 by King Ine of Wessex, at the urging of Aldhelm, Bishop of Sherborne, in whose diocese it lay.[6] It was dedicated to Saint Andrew. The only remains of this first church are some excavated foundations which can be seen in the cloisters. The baptismal font in the south transept is the oldest surviving part of the cathedral which is dated to c.700 AD.[7]

Two centuries later, the seat of the diocese was shifted to Wells from Sherborne. The first Bishop of Wells was Athelm (circa 909), who crowned King Athelstan. Athelm and his nephew Saint Dunstan both became Archbishops of Canterbury.[8] It was also around this time that Wells Cathedral School was founded.

Present structure

The present structure was begun under the direction of Bishop Reginald de Bohun, who died in 1184.[9] Wells Cathedral dates primarily from the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries; the nave and transept are masterpieces of the Early English style of architecture. It was largely complete at the time of its dedication in 1239.[10]

The bishop responsible for the construction was Jocelyn of Wells, a brother of Bishop Hugh II of Lincoln,[11] and one of the bishops at the signing of Magna Carta. Jocelyn's building campaigns also included the Bishop's Palace, a choristers' school, a grammar school, hospital for travellers and a chapel. He also built a manor at Wookey, near Wells.[12] The master mason designer associated with Jocelyn was Elias of Dereham (died 1246). Jocelyn lived to see the church dedicated, but despite much lobbying of Rome, died before cathedral status was granted in 1245. He died on November 19, 1242,[13] at Wells and was buried in the choir of Wells Cathedral.[11][12] He may have been the father of Nicholas of Wells. The memorial brass on his tomb is supposedly one of the earliest brasses in England.[12] Masons continued with the enrichment of the West Front until about 1260.

King John was excommunicated between 1209 and 1213. During this time, work on the cathedral was suspended. In this period, building technology advanced so that bigger blocks of masonry could be moved and incorporated into the walls. The effect of this technological advance can be seen on the walls of the cathedral; at a particular point in the building's walls, the blocks of stone can be seen to increase in size.

By the time the building was finished, including the Chapter House (1306),[14] it already seemed too small for the developing liturgy, in particular the increasingly grand processions. A new spate of expansive building was therefore initiated with Bishop John Drokensford starting the proceedings by heightening of the central tower and beginning a dramatic eight-sided Lady chapel at the far east end, finished by 1326.[15] Thomas of Whitney was the master mason.

Bishop Ralph of Shrewsbury followed, continuing the eastward extension of the quire, and the retro-quire beyond with its forest of pillars. He also built Vicars' Close and the Vicars' Hall, to give the men of the choir a secure place to live and dine, away from the town with all its temptations.[16] He enjoyed an uneasy relationship with the citizens of Wells, partly because of his imposition of taxes,[16] and felt the need to surround his palace with crenellated walls and a moat and drawbridge.

The appointment of William Wynford as master mason in 1365 marked another period of activity. He was one of the foremost architects of his time and, apart from Wells, was engaged in work for the king at Windsor and at New College, Oxford and Winchester Cathedral.[17] Under Bishop John Harewell, who raised money for the project, he built the south-west tower of the West Front and designed the north west, which was built to match in the early 1400s.[18] Inside the building he filled in the early English lancet windows with delicate tracery.

In the fourteenth century the central piers of the crossing were found to be sinking under the weight of the crossing tower, so the "scissor arches" (inverted strainer arches that are such a striking feature) were inserted to brace and stabilize the piers as a unit.[19]

Tudors and civil war

By the reign of Henry VII the cathedral building was complete, with an appearance much as today. Following the dissolution of the monasteries in 1541 the income of the cathedral was reduced; as a result medieval brasses were sold off, and a pulpit was placed in the nave for the first time.[20] Between 1551 and 1568, in two periods as Dean, William Turner established a Herbal garden, which has been recreated between 2003 and 2010.[21]

Elizabeth I gave both the Chapter and the Vicars Choral a new charter in 1591 which created a new governing body, consisting of the dean and eight residentiary canons. This body had control over the estates of the church as well as complete authority over its affairs, but removed its right to elect its own dean.[22]

The stability which the new charter brought came to an end with the onset of the civil war and the execution of Charles I. Local fighting led to damage to the fabric of the cathedral including stonework, furniture and windows. The dean at this time was Dr. Walter Ralegh, a nephew of the explorer Sir Walter Raleigh. He was imprisoned after the fall of Bridgwater to the Parliamentarians in 1645, brought back to Wells and confined in the deanery. His jailer was the local shoe maker and city constable, David Barrett, who caught him writing a letter to his wife. When he refused to surrender it, Mr Barrett ran him through with a sword, from which he died six weeks later,[23] on 10 October 1646 and he was buried in the choir before the deans stall. No inscription marks his grave.[24]

During the Commonwealth of England under Oliver Cromwell no dean was appointed and the building fell into disrepair. The bishop was in retirement and some clergy were reduced to performing menial tasks or begging on the streets.[20]

1660-1800

In 1661 when Charles II was restored to the throne, Robert Creyghtone, who had served as the king's chaplain in exile, was appointed as the dean and later served as the bishop for two years before his death in 1672.[25] His magnificent brass lectern, given in thanksgiving, can still be seen in the cathedral. He donated the great west window of the nave at a cost of £140.

Following Creyghtone's appointment as Bishop Ralph Bathurst, who had been president of Trinity College, Oxford,[26] chaplain to the king, fellow of the Royal Society, took over as the dean. During his long tenure restoration of the fabric of the cathedral took place. During the Monmouth Rebellion of 1685, puritan soldiers damaged the West front, tore lead from the roof to make bullets, broke the windows, smashed the organ and the furnishings, and for a time stabled their horses in the nave.[27] The work of restoration had to start all over again under Bishop Thomas Ken who was appointed in that year and served until 1691. He was one of seven bishops imprisoned for refusing to sign King James II's "Declaration of Indulgence", which would have enabled Catholics to resume positions of political power, but popular support led to his acquittal. He later refused to take the oath of allegiance to William and Mary because James II had not formally abdicated. Thomas Ken and others (known as the Non-Jurors; the older meaning of "juror" is "one who takes an oath", hence "perjurer" as "one who swears falsely") refused and were put out of office.[28] He was forced to retire to Frome.

Bishop Kidder who succeeded him was killed during the Great Storm of 1703,[29] when two chimney stacks in the palace fell on the bishop and his wife, asleep in bed.[30] This same storm wrecked the Eddystone lighthouse and blew in part of the great west window in Wells.

Victorian era and restoration

In the middle of the 1800s a major restoration programme was needed. Under Dean Goodenough the monuments were removed to the cloisters and remaining medieval paint and whitewash was removed in an operation known as the 'the great scrape'.[31] Anthony Salvin, took charge of the extensive restoration of the quire. The wooden galleries were removed and new stalls with stone canopies were placed further back within the line of the arches. The stone screen was pushed outwards in the centre to support a new organ. Since then a rolling programme of improvement to the fabric has been continued.

Original records

Three early registers of the dean and chapter of Wells - the Liber Albus I (White Book; R I), Liber Albus II (R III), and Liber Ruber (Red Book; R II, section i) - were edited by W. H. B. Bird for the Historical Manuscripts Commissioners and published in 1907. These three books comprise, with some repetition, a cartulary of possessions of the cathedral, with grants of land dating back as early as the 8th century, well before the development of hereditary surnames in England; acts of the dean and chapter; and surveys of their estates, mostly in Somerset.[32]

Architecture

The interior of the cathedral is based on three aisles, with stress being placed on horizontal, rather than vertical lines. A unique feature in the crossing are the double pointed inverted arches, known as owl-eyed strainer arches.[33] This unorthodox solution was found by the cathedral mason, William Joy in 1338,[34] to stop the central tower from collapsing when another stage and spire were added to the tower which had been begun in the 13th century.[35] The capitals in the south west arm of the transept include depictions such as a bald-headed man, a man with toothache, a thorn-extractor, and a moral tale: fruit thieves being caught and punished.

The west façade, is 100 feet (30 m) high and 150 feet (46 m) wide with niches for more than 500 medieval figure sculptures of which 300 survive. Between 1975 and 1986 the west front underwent a major cleaning and restoration programme, including Silane coating and Lime treatment for many of the statues.[36]

The West front is composed of a yellow stone, inferior oolite, of the middle Jurassic era which came from the Doulting Stone Quarry about 8 miles (13 km) to the East.[37]

Stained glass

Wells Cathedral contains one of the most substantial collections of medieval stained glass in England.[38]

Many of the windows were damaged by soldiers in 1642 and 1643. The oldest surviving are two windows on the west side of the Chapter House staircase date from 1280–90, and two windows in the south choir aisle which are from 1310–1320. The Lady Chapel range is from 1325–1330,[4] and includes images of local saint Dunstan,[38] however the east window underwent extensive repairs by Thomas Willement in 1845.[4] The choir east window is a fine Jesse Tree, which includes significant silver stain, and is flanked by two windows each side in the clerestory, with large figures of saints, all of which are from 1340–1345. The 1520 panels in the chapel of St Katherine are attributed to Arnold of Nijmegen[4] and were acquired from the destroyed church of Saint-Jean, Rouen,[38] the last panel was bought in 1953.[4] The large triple lancet to the nave west end was glazed at the expense of Dean Creyghton at a cost of £140 in 1664 and repaired in 1813. The central light was largely replaced to a design by Archibald Keightley Nicholson between 1925–1931. The main north and south transept end windows are by Powell, and were erected in the early 20th century.[4]

Fittings and monuments

The cathedral contains architectural features and fittings some dating back hundreds of years, and tombs and monuments to bishops and noblemen.

The brass lectern in the Lady Chapel is from 1661 and has a moulded stand and foliate crest. In the north transept chapel is a 17th century oak screen with columns, formerly part of cow stalls, with artisan Ionic capitals and cornice, which is set forward over chest tomb of John Godelee. There is a bound oak chest from the 14th century which would have been used to store the Chapter Seal and key documents. The Bishop's Throne dates from 1340, and has a panelled, canted front and stone doorway, and a deep nodding cusped ogee canopy over it, with 3 stepped statue niches and pinnacles. The throne was restored by Anthony Salvin around 1850. Opposite the throne is a 19th century pulpit, which is octagonal on a coved base with panelled sides, and steps up from the north aisle. The round font in the south transept is from the former Saxon cathedral, it has an arcade of round-headed arches, on a round plinth and a cover made in 1635 cover with heads of putti round sides. The Chapel of St Martin is a memorial to every Somerset man who fell in World War I.[39]

The monuments and tombs include:

- Bishop Giso, died 1088

- Bishop Bytton died 1274

- Bishop William of March, died 1302

- John Drokensford, died 1329

- John Godelee, died 1333

- John Middleton, died c1350

- Ralph of Shrewsbury, died 1363

- Bishop Harewell died 1386

- William Bykonyll died c1448

- John Bernard, died 1459

- Bishop Bekynton, died 1464

- John Gunthorpe, died 1498

- John Still died 1607

- Robert Creyghton died 1672

- Bishop Kidder, died 1703

- Bishop Hooper, died 1727

- Bishop Harvey died 1894

Clock

The Wells clock is an astronomical clock in the north transept. The surviving mechanism, dated to between 1386 and 1392, was replaced in the 19th century, and was eventually moved to the Science Museum in London, where it continues to operate. It is the second-oldest surviving clock in England.[40] The dial represents the geocentric view of the universe, with sun and moon revolving round a central fixed earth. It still has its original medieval face and, like the astronomical clock at Ottery St Mary, shows a philosophical model of the pre-Copernican universe with the earth at its centre. As well as showing the time on a 24 hour dial, it also reflects the motion of the sun and the moon, the phases of the moon, and the time since the last new moon.[41]

When the clock strikes every quarter, jousting knights move around above the clock and the Quarter jack bangs the quarter hours with his heels. An outside clock opposite Vicars' Hall, placed there just over seventy years after the interior clock, is connected with the inside mechanism.

Misericords

Wells has 64 misericords dating from 1330 to 1340, twelve of these were never completed. Although a few represent everyday scenes, such as two goats butting each other and a lamb suckling from a ewe, the subject matter of the majority is mythological.

Library

The cathedral is also famous for its library, which was built in the mid fifteenth century. Located over the East Cloister, the library holds the Chapter's collection in two rooms, with volumes published before 1800 being held in the Old Library. The library's medieval collection was destroyed during the reformation. The cathedral's earliest records are held in the Muniment Room at the southern end of the Library.[42]

The volumes held reflects the Canon's wide-ranging intellectual interests. The collection's core subject is theology, but science, medicine, history, exploration and languages are also well-represented.[42]

The library is open to the public at appointed times during summer, with a small exhibition of documents and books.[42]

Bells

Wells Cathedral has ten bells. These are the heaviest ring of ten bells in the world with a tenor bell that weighs 56 cwt. They are hung for full circle ringing in the English style. These bells are now hung in the South West Tower although originally a small number of bells were hung in the lantern. The oldest bells are the 3rd, 4th, 5th, 7th and 8th that date from 1757. Other bells have been added at various times until 1964 when the current 6th bell was hung. Details of the bells are:

- 1, weight: 7-3-12, cast: 1891 Mears & Stainbank

- 2, weight: 9-0-2, cast: 1891 Mears & Stainbank

- 3, weight: 10cwt, cast: 1757 Abel Rudhall

- 4, weight: 10¾cwt, cast: 1757 Abel Rudhall

- 5, weight: 12½cwt, cast: 1757 Abel Rudhall

- 6, weight: 15-1-14, cast: 1964 Mears & Stainbank

- 7, weight: 20cwt, cast: 1757 Abel Rudhall

- 8, weight: 23cwt, cast: 1757 Abel Rudhall

- 9, weight: 32-0-0, cast: 1877 John Taylor & Co

- 10, weight: 56-1-14, cast: 1877 John Taylor & Co

Deans of Wells

See the list of the Deans of Wells

Organ and organists

Organ

The first record of an organ dates from 1310, with a smaller organ, probably for the Lady Chapel, being installed in 1415. In 1620 a new organ, built by Thomas Dallam, was installed at a cost of £398 1s 5d, however this was destroyed by parliamentary soldiers in 1643 and another new organ was built in 1662,[43] which was enlarged in 1786,[44] and again in 1855.[45] In 1909–1910 a new organ was built by Harrison & Harrison with the best parts of old organ retained,[46] and this has been maintained by the same company since.[47]

Organists

|

|

|

Assistant organists

- Charles William Lavington 1842 - 1859

- J. Summers

- Frederick Joseph William Crowe[48] (later organist of Chichester Cathedral) c.1880

- Harry Charles Moody 1894 - 1895 (then acting organist 1895)

- Frederick William Heck 1896 - 1897[49] (afterwards organist of Bedminster Parish Church)

- W. J. Bown[50]

- R.J. Maddern Williams 1904 - 1906 (afterwards sub-organist of Norwich Cathedral).

- Kenneth J Miller 1906[51]

- F.P. Wheeldon 1908

- Frank W. Porkess

- Marmaduke Conway 1920 - 1925 (later organist of Ely Cathedral)

- Conrad William Eden 1927 - 1933 (then organist)

- J.W. Martindale-Sidwell 1938

- Michael Peterson 1948 - 1953

- Anthony Crossland 1961 - 1970

- David Anthony Cooper 1977 - 1983 (later organist of Blackburn Cathedral)

- Christopher Brayne 1983 - 1990 (later organist of Bristol Cathedral)

- David Ponsford

- Andrew Nethsingha 1990 - 1994

- Rupert Gough 1994 - 2005

- David Bednall 2002 - 2007 (Senior Organ Scholar 2002 - 2004)

- Jonathan Vaughn 2007 -

See also the List of Organ Scholars at Wells Cathedral.

Media

In filming for the 2007 Doctor Who episode The Lazarus Experiment the cathedral interior stood in for that of Southwark Cathedral. Parts of the Academy Award-nominated 2007 film Elizabeth: The Golden Age were also filmed in the cathedral.[52]

In Filming the 2007 comedy film Hot Fuzz the spiral staircase inside of the Cathedral is used for a dramatic Murder scene look.

Notable uses

In real life, the cathedral hosted the funeral of Harry Patch, the last British Army veteran of the First World War, who died in July 2009 at the age of 111.[53]

See also

- Architecture of the medieval cathedrals of England

- William Robinson Clark Dean of Taunton and prebendary of Wells 1859–1880.

- Diocese of Bath and Wells

- English Gothic architecture

- List of Bishops of Bath and Wells and precursor offices

- List of cathedrals in the United Kingdom

- List of Church of England dioceses

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Clifton-Taylor, Alec (1967). The Cathedrals of England. Thames and Hudson.

- ↑ Tatton-Brown, Tim; John Crook (2002). The English Cathedral. New Holland Publishers. ISBN 1-84330-120-2.

- ↑ Lee, Lawrence; George Seddon, Francis Stephens, (1976). Stained Glass. Spring Books. ISBN 0-600-56281-6.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 "Cathedral Church of St Andrew, Chapter House and Cloisters". Images of England. http://www.imagesofengland.org.uk/details/default.aspx?id=483287. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ↑ Adkins, Lesley; Roy Adkins (1992). A field guide to Somerset archeology. Wimborne: Dovecote Press. pp. 118–119. ISBN 0946159947.

- ↑ "Wells Cathedral". Britania.com. http://www.britannia.com/history/somerset/churches/wellscath.html. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ↑ "Virtual tour of Wells Cathedral". RE:Quest. http://www.request.org.uk/main/churches/tours/wells/font.htm. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ↑ "History & Architecture of Wells Cathedral". Britannia. http://www.britannia.com/history/somerset/churches/wellscath.html. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ↑ Powicke Handbook of British Chronology p. 251

- ↑ "History". Wells Cathedral. http://www.wellscathedral.org.uk/history/archaelogy/wellscathedral.shtml. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 British History Online Bishops of Bath. Retrieved September 23, 2007.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Dunning "Wells, Jocelin of (d. 1242)" 'Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online Edition. Retrieved November 15, 2007.

- ↑ Fryde Handbook of British Chronology p. 228

- ↑ "Wells Cathedral". Sacred destinations. http://www.sacred-destinations.com/england/wells-cathedral.htm. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ↑ "Wells Cathedral". Isle of Albion. http://www.isleofalbion.co.uk/wellscathedral/. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Local history". Wells UK. http://www.wells-uk.com/local_history.php. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ↑ page 352, English Medieval Architects A Biographical Dictionary Down to 1550, John Harvey 1984

- ↑ Somerset by Wade, G.W. & Wade, J.H. at Project Gutenberg

- ↑ "Wells Cathedral". Timeref. http://www.btinternet.com/~timeref/hpl285.htm. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Changes of monarch". Wells cathedral. http://www.wellscathedral.org.uk/history/presentbuilding/changesofmonarch.shtml. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ↑ Adler, Mark (May 2010). Mendip Times: pp. 36–37.

- ↑ "Colleges: The cathedral of Wells, A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 2 (1911)". British History Online. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=40953. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ↑ "Hollywood parodies real life drama in Wells". BBC Somerset. http://www.bbc.co.uk/somerset/content/articles/2007/10/24/elizabeth_feature.shtml. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ↑ Lee, Sidney (2001). Dictionary of National Biography. Adamant Media Corporation. pp. 206–207. ISBN 1402170645.

- ↑ Lehmberg, Stanford E. (1996). Cathedrals Under Siege: Cathedrals in English Society, 1600-1700. Penn State Press. p. 55. ISBN 0271014946.

- ↑ Hopkins, Clare (2005). Trinity: 450 Years of an Oxford College Community. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 161. ISBN 0199518963.

- ↑ "The Monmouth rebellion and the bloody assize". Somerset County Council. http://www.somerset.gov.uk/archives/ASH/Monmouthreb.htm. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ↑ "Wells Cathedral". Magic Statistics. http://magicstatistics.com/2005/10/02/wells-cathedral/. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ↑ "November 27th". Every-day book. http://www.uab.edu/english/hone/etexts/edb/day-pages/331-nov27.html. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ↑ "Newsletter no. 35, Spring 2000:". The Center & Clark Newsletter On Line. http://www.humnet.ucla.edu/humnet/c1718cs/Nltr35.html. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ↑ "Restoration". Wells Cathedral. http://www.wellscathedral.org.uk/history/presentbuilding/restoration.shtml. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ↑ Theoriginalrecord.com, Liber Albus I (White Book; R I), Liber Albus II (R III), and Liber Ruber (Red Book; R II, section i) indexed by surname: scans available online.

- ↑ "The Medieval Stonemason". BBC History. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/middle_ages/architecture_medmason_02.shtml. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ↑ "Why ancient cathedrals stand up: The structural design of masonry" (PDF). Ingenia. http://www.ingenia.org.uk/ingenia/issues/issue10/heyman.pdf. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ↑ Sale, Richard (2007). Somerset: A landmark visitors guide (3rd Ed). Ashbourne: Landmark Publishing. pp. 149–150. ISBN 9781843063285.

- ↑ Caroe, M.B. (1985). "Wells Cathedral Conservation of Figure Sculptures 1975-1984". Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology (Association for Preservation Technology International (APT)) 17 (2): 3–13. doi:10.2307/1494129. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0044-9466%281985%2917%3A2%3C2%3AWCCOFS%3E2.0.CO%3B2-C. Retrieved 2008-02-12.

- ↑ "Wells Cathedral". Open University Geological Society. http://www.ougswessex.fsnet.co.uk/rep2003/wells.html. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 "The Medieval Stained Glass of Wells Cathedral" (PDF). British Academy. http://www.britac.ac.uk/pubs/review/_pdfs/09/07-ayers.pdf. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ↑ Leete-Hodge, Lornie (1985). Curiosities of Somerset. Bodmin: Bossiney Books. p. 20. ISBN 0906456983.

- ↑ "Wells Cathedral clock, c.1392". Science Museum. http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects/time_measurement/1884-77.aspx. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ↑ "Wells Cathedral". Isle of Albion. http://www.isleofalbion.co.uk/wellscathedral/. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Wells Cathedral - Library & Archives

- ↑ "Somerset, Wells Cathedral of St. Andrew, Dean & Chapter Of Wells N0 6890". National Pipe Organ Register (NPOR). http://www.npor.org.uk/cgi-bin/Rsearch.cgi?Fn=Rsearch&rec_index=N06889. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ↑ "Somerset, Wells Cathedral of St. Andrew, Dean & Chapter Of Wells N06890". National Pipe Organ Register (NPOR). http://www.npor.org.uk/cgi-bin/Rsearch.cgi?Fn=Rsearch&rec_index=N06890. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ↑ "Somerset, Wells Cathedral of St. Andrew, Dean & Chapter Of Wells N06891". National Pipe Organ Register (NPOR). http://www.npor.org.uk/cgi-bin/Rsearch.cgi?Fn=Rsearch&rec_index=N06891. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ↑ "Somerset, Wells Cathedral of St. Andrew, Dean & Chapter Of Wells N06892". National Pipe Organ Register (NPOR). http://www.npor.org.uk/cgi-bin/Rsearch.cgi?Fn=Rsearch&rec_index=N06892. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ↑ "Somerset, Wells Cathedral of St. Andrew, Dean & Chapter Of Wells N06893". National Pipe Organ Register (NPOR). http://www.npor.org.uk/cgi-bin/Rsearch.cgi?Fn=Rsearch&rec_index=N06893. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ↑ Dictionary of Organs and Organists. First Edition. 1912. p264

- ↑ Dictionary of Organs and Organists. First Edition. 1912. p.286

- ↑ Dictionary of Organs and Organists. First Edition. 1912. p251

- ↑ Dictionary of Organs and Organists. First Edition. 1912. p.309

- ↑ "Hollywood parodies real life drama in Wells". BBC Somerset. http://www.bbc.co.uk/somerset/content/articles/2007/10/24/elizabeth_feature.shtml. Retrieved 2008-02-12.

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/8186578.stm

Further reading

- Ayers, Tim (2004). The Medieval Stained Glass of Wells Cathedral. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780197262634.

- Cockerell, Charles Robert (1851). Iconography of the West Front of Wells Cathedral. J. H. Parker. http://books.google.com/?id=RioEAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=Iconography+of+the+West+Front+of+Wells+Cathedral.

- Malone, Von Carolyn Marino (2004). Façade as Spectacle: Ritual and Ideology at Wells Cathedral. Brill Publishers. ISBN 9004138404.

- Reid, R.D. (1963). Wells Cathedral. Friends of Wells Cathedral. ISBN 0902321110.

External links

|

||||||||